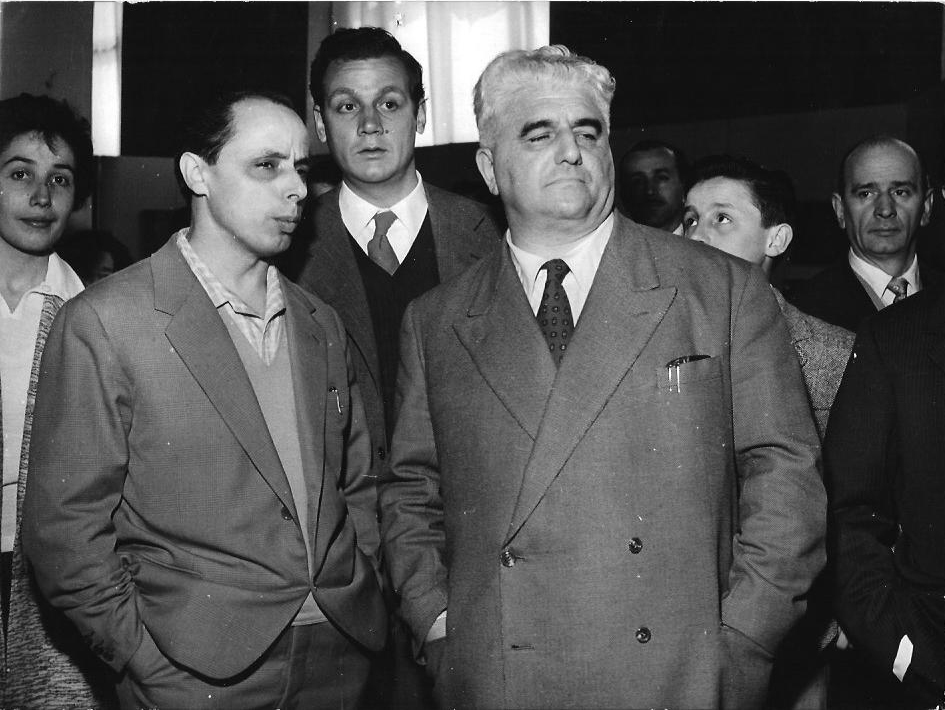

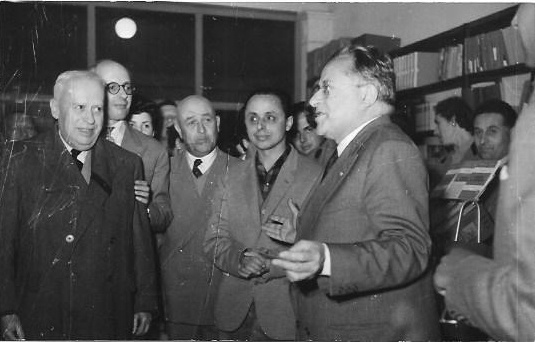

Impegno politico, civile e sociale

“Cosa fanno gli artisti per la classe operaia? Risposi: Noi cerchiamo di esprimere la volontà per un mondo migliore…più giusto…”

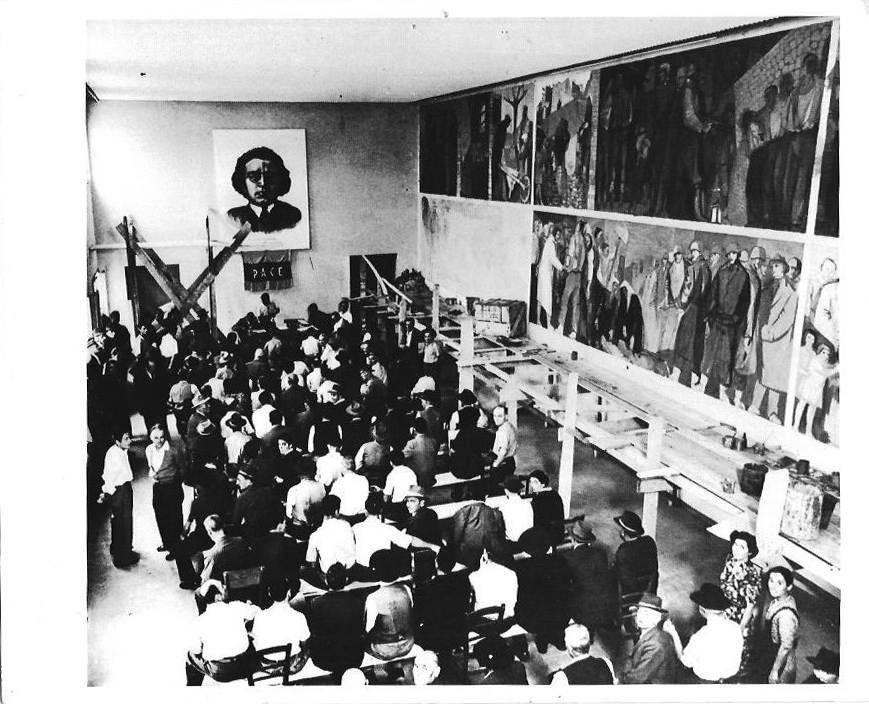

(Aldo Borgonzoni, “Sciopero alla Barbarra”, 1957, Courtesy Archivio e Centro Studi Aldo Borgonzoni)

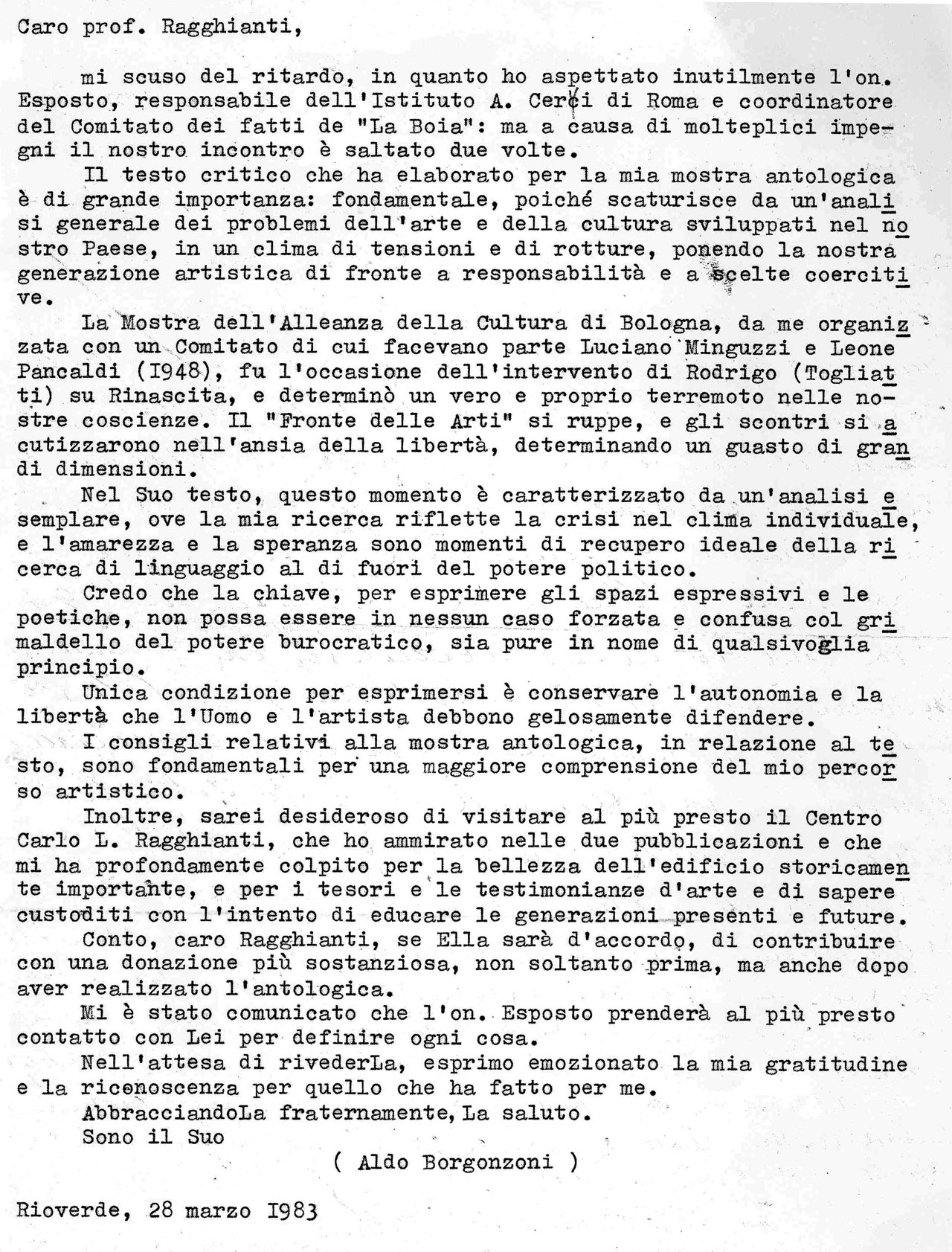

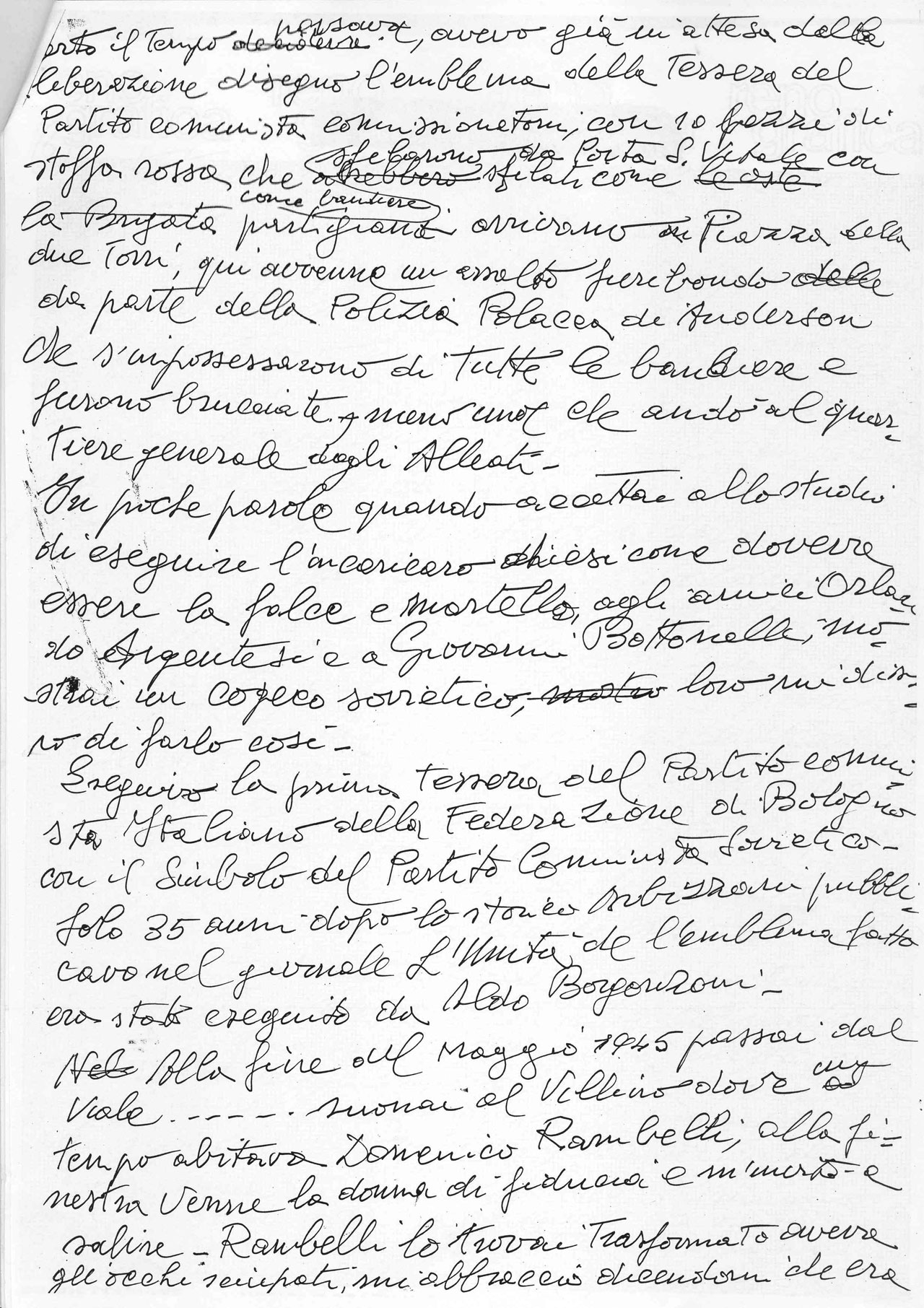

La vita e l’arte di Aldo Borgonzoni si distinguono per il coerente impegno etico e ideologico nei confronti della libertà e di qualsiasi sopruso che ledesse la dignità dell’uomo, in particolare dei più umili e deboli. Antifascista, con generosità spirituale e umanitaria contribuì, alla salvezza di Virgilio Guidi nel periodo della Resistenza; prese la tessera del Partito Comunista Italiano, ma proprio da esso ebbe le prime delusioni professionali, come testimonia la lettera dattiloscritta e indirizzata dall’artista a Carlo Ludovico Raggianti, il 28 marzo 1983.

“Pochi anni dopo, la guerra devastò il mondo, producendo nella nostra epoca apparentemente caratterizzata dalla ragione, le peggiori efferatezze del millennio al crepuscolo. I campi nazisti di sterminio costellarono l’intera Europa, l’Italia fascista mandò al macello la gioventù e alla ragione si sostituì la cupa violenza dell’uomo sull’uomo; e così solo nel 1943, con la liberazione di Roma e lo sviluppo del movimento di opposizione, si riaccese la nostra speranza. In quell’anno, causa i bombardamenti alleati e la carestia che colpivano duramente Bologna, ritornai a Medicina con la famiglia ritrovando il Maestro Guidi. L’artista per gli stessi motivi si era trasferito in campagna, nella Villa dei Lenzi a Buda, una frazione del mio paese. Al tempo il movimento partigiano, molto attivo in zona, era diretto da Orlando Argentesi, amico fraterno fin dall’adolescenza. Una mattina di settembre, questi mi comunicò che Guidi era stato condannato a morte, poiché aderente e acceso propagandista della Repubblica di Salò; mi opposi fermamente pregandolo di considerare che non aveva fatto nulla d’irreparabile e che comunque doveva prevalere il giudizio ampio e positivo sulla sua opera. Dopo accese discussioni la sentenza fu convertita in espulsione entro tre giorni dal territorio. Al momento convenuto, e dopo ripetute lezioni di bicicletta, Guidi, la sua allieva, accompagnata dal marito ed io, lasciammo Buda, raggiungendo a tarda sera Chioggia e quindi con un traghetto Venezia. Qui gli intellettuali legati alla Resistenza lo strapparono definitivamente alla persecuzione nonostante che il Maestro, frequentando lo storico Caffè Florian, continuasse ad affermare, che i tedeschi avrebbero rovesciato, con l’arma segreta, le sorti della guerra.”

(A. Borgonzoni, Virgilio Guidi e Domenico Rambelli fra arte e ideologia, in C. Spadoni, a cura di, Il Naturalismo espressionista di Aldo Borgonzoni, Faenza, Edizioni Silvio Pellico, 1995)